by Justina Ireland

First sentence: ” The day I came squealing and squalling into the world was the first time someone tried to kill me.”

Support your local independent bookstore: buy it there!

Content: There’s a lot of violence and some swearing and some references to the sex trade. It’s in the Teen section (grades 9+) but I think it’d be good for a younger reader, if they were interested.

It’s the 1880s, and America is still trying to overcome the zombie — they call them shamblers — infestation that began during the Civil War. Sure, the war kind of petered out, but the south is pretty much wiped out, given over to shamblers. And the east coast is partially fortified, but mostly because the government ships blacks and native peoples into schools where they get training to be, well, shambler killers.

Our main character is Jane McKeene, a half-black girl from a plantation in Kentucky, who has attended Miss Preston’s School of Combat in Baltimore. She’s set to graduate and become an Attendant, protecting some rich white woman, when she discovers the seedy underbelly of the city. Which puts her into some definite hot water. And lands her in the West, where there are no rules. Especially for someone like her.

I loved this one. Seriously. It’s a lot of fun, first of all (and I don’t really read zombie books), and I really liked the alternative history that Ireland created. It felt like it could have been a real history, just with zombies. But, I also really liked that it wasn’t all fluff and nonsense, that there were some real issues of racism and sexism and even zealotry in there. Things that would make for a good book discussion.

And while there will most likely be a sequel, the story did come to a satisfactory conclusion. Which is always nice.

A really really good book.

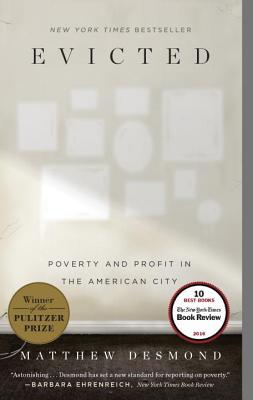

by Matthew Desmond

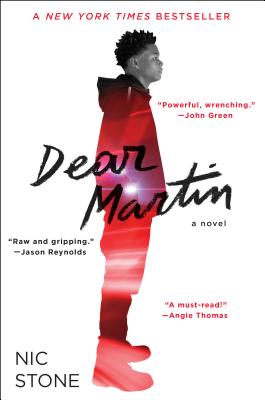

by Matthew Desmond by Nic Stone

by Nic Stone