It’s Martin Luther King Jr Day tomorrow, and we’re probably celebrating by going to see Selma. And I know I’m a bit early for Black History Month, but I thought I’d do a list of books that celebrate the depth and breadth of the African-American experience. I don’t think I came up with one that’s really comprehensive, especially since I tend toward the historical fiction, but it’s a start.

Historical:

Sugar, by Jewell Parker Rhodes: “It’s 1871, and slavery is supposed to be over. However, for ten-year-old Sugar, on a sugar plantation in Louisiana, it doesn’t feel like it. Sure, the former slaves are free to go if they can, but they’re paid so little that it’s almost impossible for them to leave.”

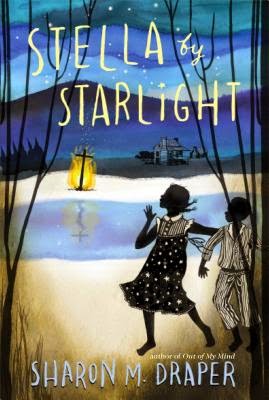

Stella By Starlight, by Sharon M. Draper: “It’s 1932, North Carolina. The whole country is in the throes of the Great Depression, Franklin D. Roosevelt is running for office. For Stella and her family, this doesn’t really matter. They’re more concerned about making ends meet. And avoiding the local Klu Klux Klan.”

Mare’s War, by Tanita S. Davis: “As they start driving, Mare starts talking about her past: what made her run away from Bay Slough, Alabama and join up in the Women’s Army Corps near the end of World War II. Her experiences in both a segregated south and a 1940s midwest, not to mention in the army. The chapters alternate between then — Mare’s history — and now — the road trip — and as the book unfolds, we learn more about all three of our characters”

Flygirl, by Sherri L. Smith: “Ida Mae Jones has always wanted to fly. Ever since she was put behind the wheel of her daddy’s plane and taught how, she knew that this was what she was born to do. Except, she’s an African American and lives in the outskirts of New Orleans. Not only can she not get a pilot’s license because she’s a woman; she can’t get one because she’s the wrong color.”

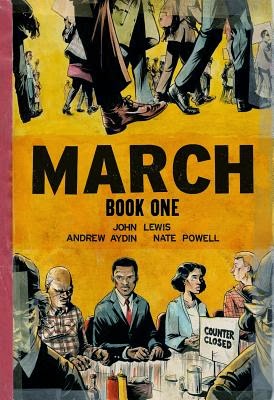

March: Book One, by John Lewis:This is a slim graphic memoir, telling the first part of Congressman John Lewis’s story. This volume starts with his childhood in Alabama, and goes through the Nashville sit-ins that he participated in. My favorite thing about this memoir was the framing: It opens with Lewis waking up the morning of Obama’s first inauguration, and the story unfolds as Lewis is remembering his path to D.C. as he tells it to a couple of constituents who have stopped by his office.

The Watsons Go to Birmingham, by Christopher Paul Curtis: “: This was a terrific book — a wonderful portrayal of a black family in early 1960s Flint, MI. It was hilarious (all the way through the end): the narrator called his family the “Wacky Watsons” and they were.”

Brown Girl Dreaming, by Jacqueline Woodson: “Her childhood begins in Ohio, but mostly it’s spent in South Carolina, with her grandparents, and in Brooklyn, where her mother finally settled with Jacqueline and her brothers and sister. I kept trying to figure out the timeline (if she was born in 1963, then it must be…) but eventually, I just gave up and let myself get absorbed in the story.”

No Crystal Stair, by Vaunda Micheaux Nelson: “The book follows Lewis and his family — his parents, and a couple of his brothers — through most of the 20th century, beginning in 1906, through his many failed ventures to his inception and success in the bookstore. It’s fascinating to read and think about: Lewis’s big thing was that black people can’t stop being Negros — that is, defined by white people — until they know their history. Which means: they need to read. And read about their people.”

Contemporary:

Out of My Mind, by Sharon M. Draper: “Melody is very, very smart. She’s known words and ideas and concepts since she was very little. She loves music, and can see colors when it plays. But, she has no way to tell anyone any of this. Melody has cerebral palsey, and while she can hear and understand, she just can’t communicate. Which is incredibly frustrating to her.”

Peace, Locomotion, by Jacqueline Woodson: “The book is a series of letters from Lonnie — aka Locomotion — to his younger sister Lili. They’ve been put in different foster homes after a fire killed their parents. The loss is still there, at least for Locomotion, and he’s made it his “job” to help Lili not forget his parents.”

Ghetto Cowboy, by G. Neri; “Living in Detroit, twelve-year-old Cole and his mom are scraping by. Sure, he doesn’t go to school that often, but he’s okay. Until the day he gets caught, his mom flips, and drives him to Philadelphia to live with a father Cole has never met. Once he gets to Philly, angry about being abandoned (as he sees it), by his mom, he decides he will have nothing to do with his father, or the stables he runs in North Philly.”

Saving Maddie, by Varian Johnson: Joshua Wynn is a good guy. He doesn’t drink, he doesn’t smoke, he doesn’t party, he doesn’t have sex. He chooses leading his church’s youth group over playing on the school basketball team. Granted, he’s the preacher’s kid, and there’s an enormous amount of pressure on Joshua to be good. And Joshua’s mostly okay with that. That is, until Maddie Smith — his best childhood friend who moved away when she was 13 — moves back into town.”

So, I know I left off a lot. What are some of the best ones?