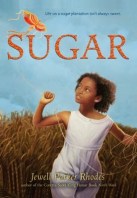

by Jewell Parker Rhodes

First sentence: “Everybody likes sugar.”

Support your local independent bookstore: buy it there!

Bought and signed by the author at KidLitCon 2014

Content: This one would be appropriate (and probably okay, difficulty-wise) for kids third grade and up. It’s in the middle grade section (grades 3-5) of the bookstore.

It’s 1871, and slavery is supposed to be over. However, for ten-year-old Sugar, on a sugar plantation in Louisiana, it doesn’t feel like it. Sure, the former slaves are free to go if they can, but they’re paid so little that it’s almost impossible for them to leave. And then the plantation owner, Mr. Wills, decides that he needs more workers, so he hires some Chinese to come and supplement the former slaves.

For Sugar, her life revolves around sneaking out to play with Billy, the owner’s son, and trying not to get under Mrs. Beale’s feet. And planting and cutting sugar cane. Once the Chinese arrive, however, Sugar’s world is expanded: one of them speaks English and she befriends them. In fact, she is the bridge that gets the whole working community to work together rather in competition. There’s a passage about halfway through that pretty much sums up what I think Rhodes was getting at in this book:

“How come I ca’t decide who I can see? How come I can’t decide my friends?”

“We don’t trust these men, Sugar.”

“I like Chinamen. Reverend, don’t you preach ‘Treat folks like you want to be treated’?”

“Well, now,” says Reverend, not looking at me, twiddling his thumbs.

“Sugar,” says Mister Beale, “folks get along best with folks like them. Always been that way.”

“Seems cowardly.”

Of course, things aren’t easy for Sugar and her friends: it is 1871 in the South, and white people — especially the former Overseer — are reluctant to change and adapt. There is some tragedy in this book, but it is a middle grade book, after all, and the tragedy is kept simple and appropriate.

It’s the overall message of friendship and inclusion that made this slim historical fiction book worth reading.