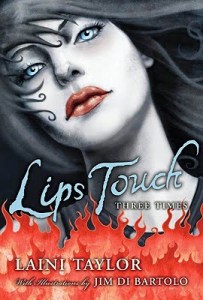

by Laini Taylor/Illus. by Jim Di Bartolo

by Laini Taylor/Illus. by Jim Di Bartolo

ages: 12+

First sentence: “There is a certain kind of girl the goblins crave.”

Review copy picked up from the ARC exchange table at KidlitCon 09.

Support your local independent bookstore: buy it there!

Wow.

Oh, I knew Laini Taylor had a fabulous imagination, having adored both Blackbringer and Silksinger, but, really: wow.

This one is three short stories in which the only connection is the act of kissing. Taylor explores what that “means”, but because it’s Laini Taylor, the exploration is not what you’d expect. Or maybe you would, if you’d read her other stuff. In short, it’s weird, wild, entrancing and just plain fabulous. Without giving too much away…

The first story, “Goblin Fruit”, takes something that every girl wants — to be noticed by the popular, cute boy — and turns it ever-so-slightly sinister. Kizzy has a weird immigrant family, one that she’s embarrassed about. It’s all she can do to avoid their practices, beliefs, superstitions, especially those of her (now-dead) grandmother, who believed quite strongly that there are goblins out there waiting to capture your soul. Kizzy tries to live a normal life, even from the sidelines of her high school, but she wants. Wants — to be popular, to be in the arms of the cute boy — so badly it’s palpable. So, when Jack Husk — beautiful, amazing, wonderful Jack Husk — shows up and pays attention to her, she goes with it. It’s got a bit of an open ending: what really does happen to Kizzy, but it doesn’t really matter. In this story, it’s the getting there that counts.

The second story, “Spicy Little Curses”, was my favorite. Taylor played off of Hindu religion and myth on this one, not only setting the story in Imperialist India, but giving us a devil in Hell who thrives off of making life (and death) miserable for humans. There’s a human liaison to Hell who tries to temper what this devil does, but one day — in exchange for twenty two souls — she allows the devil to curse the daughter of the Political Agent. The curse: if she ever speaks, she’ll kill everyone in the sound of her voice. She manages never to speak, but of course, she grows up into a lovely young woman and a soldier falls in love with her. There is not a happy outcome (again, of course), but the twists and turns and the language (oh, the language!) make it simply a joy to read.

And, finally, “Hatchling”. It’s the longest of the three stories, the most developed, the most interesting world-building that I’ve read in a while. Taylor takes were-lore and vampire-lore and develops it in a new and fascinating way in giving us the Druj. Not quite werewolves (and yet they shape shift), not quite vampires (and yet they use and abuse humans for their own pleasure), they terrorize and terrify humans. Mab was one of those, and for some reason, she managed to escape from the Queen. She was pregnant at the time and with her daughter, Esme, she has been in hiding ever since. Fourteen years later, Esme wakes up one morning with one blue eye and one brown eye. This not only terrifies Mab, but leads Emse to the destiny that she never knew she had, changing the way the Druj interact with each other and the world in the process.

I know I didn’t quite capture the wonderfulness that is this book. But it truly is amazing.