I have had a hard time with Latin@ (see, turtlebella? I do learn!) literature in the past. Magical realism and I have not been good friends. I hear over and over again people loving these books and I read them, and… I think they’re just weird.

I have had a hard time with Latin@ (see, turtlebella? I do learn!) literature in the past. Magical realism and I have not been good friends. I hear over and over again people loving these books and I read them, and… I think they’re just weird.

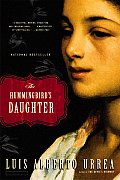

But this one, by Louis Alberto Urrea, is different. Maybe it’s because though the magic is there, it’s not nearly as prevalent as in other books. But I think it’s mainly because it’s a work of historical fiction, and more than that: it’s a work of love.

The story is that of Urrea’s great-aunt Teresa. She was the bastard daughter of Thomás Urrea, a patrón of a ranch in Mexico. She flies under the radar for the most part during her early life, living in squalor and unloved by her aunt (her mother left when Teresa was small) until she came under the guidance of the local healer, Huila. Then she learns the secrets of the Indians (of which she is half), and how to heal and dream and guide. Eventually, after the ranch moves north to a different location, he and her father become reconciled (though it’s more like “become introduced”) and she moves in the main house with him. She learns to read, her life is pretty quiet. Until one day, when a vaquero attacks her in her sacred grove of trees. She dies… and is resurrected. And from there, we see the evolution of Santa Teresa, the woman who will help the masses rise in revolution against the dictatorship.

Writing that, it sounds very simple, but this book is anything but. It’s immense. It’s lyrical. It’s funny. It’s sorrowful. The one thing I could tell is that Urrea really cared about his subject. The love and respect he has for Teresa, as well as all the years of research he did, is evident in every page. And because of that, the book (for me, at least) soars. I couldn’t put it down. I hung on every beautiful descriptive word. An example:

Only rich men, soldiers and a few Indians had wandered far enough from home to learn the terrible truth: Mexico was too big. It had too many colors. It was noisier than anyone could have imagined, and the voice of the Atlantic was different than the voice of the Pacific. One was shrill, worried, and demanding. The other was boisterous, easy to rile into a frenzy. The rich men, soldiers, and Indians were the few who knew that he east was a swoon of green, a thick-aired smell of ripe fruit and flowers and dead pigs and salt and sweat and mud, while the west was a riot of purple. Pyramids rose between llanos of dust and among turgid jungles. Snakes as long as country roads swam tame beside canoes. Volcanoes wore hats of snow. Cactus forests grew taller than trees. Shamans ate mushrooms and flew. In the south, some tribes still went nearly naked, their women wearing red flowers in their hair and blue skirts, and their breasts hanging free. Men outside the great Mexico City ate tacos made of live winged ants that few away if the men did not chew quickly enough.

It’s books like this that make me glad I read as much as I do.

I really enjoyed this when I read it!

LikeLike

It sure sounds like an interesting book.

LikeLike

I just read this one a few months ago and I loved his writing-it was just beautiful. I felt a wide range of emotions as I read it, and the writing was beautiful.

LikeLike

Oh so glad you enjoyed this one. It was one of my favorite reads of 2007. I was so moved by the characters and I even shed a couple of tears.

LikeLike

This doesn’t sound like my type of book but I am glad it turned out well for you!

LikeLike

I’ve checked this one out of the library. I almost left it on the shelf when I saw that it wasn’t very short, but I shall persevere.

LikeLike