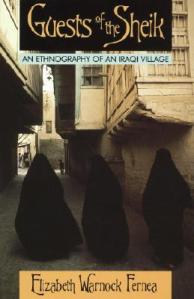

An Ethnography of an Iraqi Village

An Ethnography of an Iraqi Village

by Elizabeth Warnock Fernea

ages: adult

First sentence: “The night train from Baghdad to Basra was already hissing and creaking in its tracks when Bob and I arrived at the platform.”

Support your local independent bookstore: buy it there!

I’m perfectly sure, even with Amira’s high recommendation, that I would have never picked up this book without it being chosen as a book group selection. I am also perfectly sure that, even though it took me a lot longer to read than I wanted it to (for various reasons), it’s a fascinating look at a specific segment of of the Iraqi women population in a specific time in history.

Our author, amazing woman that she is, was brave enough to spend the first years of her marriage in a backwater tribal village in southern Iraq in 1957 and 1958. Her husband, Bob, was there to do some research, and she went along for the ride. It was good, as well, since Bob had no access to half the population: the women. Through trial and error, Elizabeth (or Beeja as they referred to her) made her way through the intricacies of daily life for a Shiite Muslim woman in that particular tribe. It was an interesting insight to the Islamic faith, to the traditions and strictures and customs of both the faith as well as the tribe.

That’s one of the things I had to keep reminding myself: this ethnography (so hard to spell!) is of a particular village in a particular time, and while it’s fascinating, it really can’t be applied broadly. I kept wondering how things have changed, not just for the village, but for women in Iraq in general.

Given that, it was an interesting story. I kept admiring Beeja for her gumption: I’m not sure, newly married, if I would have been that adventuresome. (Yes, I want to travel, but generally “travel” for me includes flushing toilets and mattresses.) But, she did what any sensible person would do: she threw herself into her situation and made the best of it. Can’t ask for more than that. It was interesting to read about her ups and downs of adapting, and how her relationships with the women in the village evolved and flourished in spite of the cultural (and, initially, linguistic) barriers.

But it wasn’t until the end of the book that I found something that truly resonated with me:

How many years would it take, I wondered, before the two worlds began to understand each other’s attitudes towards women? For the West, too, had a blind spot in this area. I could tell my friends in America again and again that the veiling and seclusion of Eastern women did not mean necessarily that they were forced against their will to live lives of submission and near-serfdom. I could tell Haji again and again that the low-cut gowns and brandished freedom of Western women did necessarily mean that these women were promiscuous and cared nothing for home and family. Neither would have understood, for each group, in its turn, was bound by custom and background to misinterpret appearances in its own way.

For better or for worse, this still is the case. And, at the very least, helping bridge that misinterpretation is something good that this book, even out-of-date as it is, can do.

This actually sounds like something I'd really, really like!

LikeLike